Now, I’m risking the ire of the extremely helpful and generous New Zealand International Film Festival team here, but I’m going to recommend an approach to festival-going that will probably reward you more than it will them. Here goes: don’t book for anything. Don’t plan your life around any particular screening of any particular film. Especially, don’t book for anything because that’s the one all your mates are going to.

Try this instead. Wake up on any given morning during the festival, feel like watching a movie, have a look through the festival calendar in the middle of the programme (or the handy-sized mini-guide, available soon) and pick a something you fancy based on the title. Or the cinema closest to you. Or the cinema furthest away. Or close your eyes and jab a finger at the page. Either way, step out of your comfort zone and try something new. You won’t regret it. Well, you might, but probably not for long.

Every year, this is kind of what I do when I ask the festival publicity team for help with this preview. Give me a stack of screener DVDs, I say, or those new-fangled internet links where I have to watch a film sitting at my desk. No, don’t tell me what they are. Let me guess. Some of my favourite festival experiences have come watching films I knew nothing about, but for those of you who are going to ignore my advice and, um, take my advice, here are some notes on the films I’ve already seen, in no particular order.

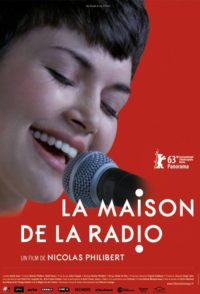

I’m a radio-head from my childhood. I love radio, listening to it, appearing on it, making it. I love looking at studios, perving at microphones, the red lights that go on when the mics are live, the silently ticking clocks. Watching Nicolas Philibert’s The House of Radio, I was a pig in shit. I don’t think I’ve been as blissed out as this watching a film for ages. It’s one day in the life of Radio France, where seemingly dozens of stations share a giant Parisian cathedral dedicated to the wireless. News, talk, culture, music – classical, jazz and hip-hop. Philibert’s polite camera peers into their studios and their offices, even the Tour de France correspondent reporting live from the back of a motorbike.

I’m a radio-head from my childhood. I love radio, listening to it, appearing on it, making it. I love looking at studios, perving at microphones, the red lights that go on when the mics are live, the silently ticking clocks. Watching Nicolas Philibert’s The House of Radio, I was a pig in shit. I don’t think I’ve been as blissed out as this watching a film for ages. It’s one day in the life of Radio France, where seemingly dozens of stations share a giant Parisian cathedral dedicated to the wireless. News, talk, culture, music – classical, jazz and hip-hop. Philibert’s polite camera peers into their studios and their offices, even the Tour de France correspondent reporting live from the back of a motorbike.

Andrew Bujalski’s Computer Chess starts out like a one joke mockumentary about a geek-meeting in the early 80s, where programmers face off against each other in an aspie battle for chess supremacy. Shot in authentic grainy black and white video, Bujalski takes his film in some surprising and mystical directions, ending on a note of universal wonder at, I don’t know, things.

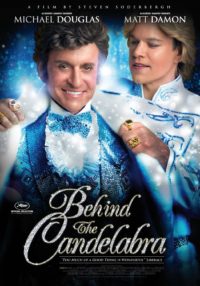

Behind the Candelabra is directed by Steven Soderbergh (photographed and edited by him too under his customary aliases Peter Andrews and Mary Ann Bernard) from a script by Richard La Gravanese about the predatory and manipulative romantic practices of the closeted entertainer Liberace. Brilliant Matt Damon plays the spurned lover Scott Thorson and Michael Douglas is the diamond and fur-clad pianist. Everything that Soderbergh does here elevates a fairly run-of-the-mill screenplay, and the results are never less than entertaining. Look out for screen legend Debbie Reynolds and note that this film was the late Marvin Hamlisch’s final screen credit.

Behind the Candelabra is directed by Steven Soderbergh (photographed and edited by him too under his customary aliases Peter Andrews and Mary Ann Bernard) from a script by Richard La Gravanese about the predatory and manipulative romantic practices of the closeted entertainer Liberace. Brilliant Matt Damon plays the spurned lover Scott Thorson and Michael Douglas is the diamond and fur-clad pianist. Everything that Soderbergh does here elevates a fairly run-of-the-mill screenplay, and the results are never less than entertaining. Look out for screen legend Debbie Reynolds and note that this film was the late Marvin Hamlisch’s final screen credit.

In Oh Boy, Tom Schilling’s Berlin student drop-out Niko Fischer mooches around the city trying to find a cup of coffee, thwarted by friends, family and strangers across one long hot day. There’s something about black and white that makes this sort of thing seem like it has more going on than it has – heirs and graces. Similarly, I enjoyed Frances Ha, and I didn’t mind this, but I do wonder how much notice we would take if they weren’t shot to look like Manhattan.

High School in Kazakhstan is no walk in the park if Harmony Lessons is anything to go by. The bullies that torment sensitive young Aslan (Timur Aidarbekov), learn their trade from the adults as we discover once the cops get involved. First time writer-director Emir Baigazin is stronger at the latter than the former – there are plenty of “woah” images and his compositions are always splendid but the script is a bit obvious. NB: Also features some startlingly authentic violence.

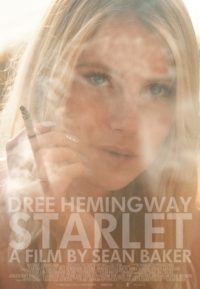

Starlet has plenty of its own brand of authenticity – the San Fernando Valley adult film industry provides a background to a rather sweet story of a young porno actress (Dree Hemingway) who befriends an elderly woman (only-time actress and former professional astrologer Besedka Johnson). There’s something beguiling about discovering nuggets of generosity in the unlikeliest of places and few films these days are founded on characters trying to be nice to each other. Winning is how I’d describe it.

Starlet has plenty of its own brand of authenticity – the San Fernando Valley adult film industry provides a background to a rather sweet story of a young porno actress (Dree Hemingway) who befriends an elderly woman (only-time actress and former professional astrologer Besedka Johnson). There’s something beguiling about discovering nuggets of generosity in the unlikeliest of places and few films these days are founded on characters trying to be nice to each other. Winning is how I’d describe it.

Also winning, literally and figuratively, is The Rocket, an Australian film set in Laos. An indefatigable young boy, Sittiphon Disamoe, believes himself to be cursed with rotten luck and, through most of the film, fate proves him right. He never gives up, though, and Kim Mordaunt’s engaging film builds to an explosive and satisfying climax. Crowd-pleasing.

Curtis Vowell and Sophie Henderson’s Fantail is a first feature that shows a lot of promise – and more than a few rewards of its own. Henderson – who wrote the script based on her own one-woman show – plays Tania, working the graveyard shift at a deadbeat petrol station, dreaming of better things for her and her younger brother (Jahalis Nhamotu). Its faults are forgiveable – a stage-bound structure and a plot that loses its way in the final third – when what works works so well. Everyone appears to be cast against type which is a very pleasant surprise for a New Zealand feature.

I really, really – no, I mean really – enjoyed the Horrocks’ family’s Venus: A Quest, in which cartoonist Dylan travels half way across the world to find out about the family links to astronomer Jeremiah Horrocks, who discovered the Transit of Venus in 1639. The whole film, cleverly constructed by Roger and Shirley Horrocks, who also directs, turns out to be about curiosity and discovery and how we should never stop asking questions and searching for answers. Their journey takes them to Liverpool, Bolton, Wellington and Tolaga Bay, where the community there witnesses the 2012 Transit and remembers the arrival of Captain Cook and his ship full of scientists.

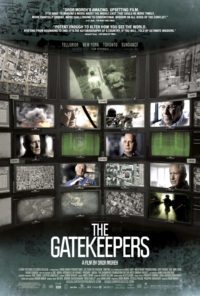

Political and activist documentary is well-represented as always – the Gibney docos are already getting well-justified kudos. The most important story, in my opinion, is Dror Moreh’s The Gatekeepers in which pillars of the Israeli establishment – all former heads of the Shin Bet internal security service – break ranks with their political masters and tell the awful truth about how Israel has been defending itself over the last 40 years. I saw it last year and thought it was incendiary, and yet somehow it hasn’t exploded yet. I can’t recommend it highly enough – exemplary.

Political and activist documentary is well-represented as always – the Gibney docos are already getting well-justified kudos. The most important story, in my opinion, is Dror Moreh’s The Gatekeepers in which pillars of the Israeli establishment – all former heads of the Shin Bet internal security service – break ranks with their political masters and tell the awful truth about how Israel has been defending itself over the last 40 years. I saw it last year and thought it was incendiary, and yet somehow it hasn’t exploded yet. I can’t recommend it highly enough – exemplary.

Fire in the Blood is also powerfully argued, if a little too reliant on documentary clichés to tell its story. Good job the story is so important. Dylan Mohan Grey’s film is about the scandalous withholding of Aids drugs from Africa in the 90s and on into this century. I had naively thought that providing antiretroviral drugs to Africa was George W. Bush’s one great saving grace, but it turns out that his plan was instantly hijacked by the giant pharmaceutical companies and he allowed it to be hijacked. 10 million people died who didn’t need to. Unless protecting obscene corporate profits is a need.

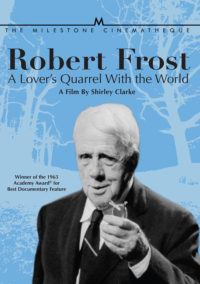

Tucked away in the dark recesses of the programme, easily missed I suspect, are two documentaries by Shirley Clarke, both about great American artists, both made many years ago and both revived so we may see them again. I liked Robert Frost: A Lover’s Quarrel with the World more than Ornette: Made in America (about Ornette Coleman) but that’s because I like Frost’s poetry more than I like Coleman’s music. The Frost film won the Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1964, largely I suspect because of Frost’s twinkly personality, undimmed after 88 years. It was an age when films about poets could win Academy Awards and poets could read a poem without it taking longer to explain than it takes to read.

Tucked away in the dark recesses of the programme, easily missed I suspect, are two documentaries by Shirley Clarke, both about great American artists, both made many years ago and both revived so we may see them again. I liked Robert Frost: A Lover’s Quarrel with the World more than Ornette: Made in America (about Ornette Coleman) but that’s because I like Frost’s poetry more than I like Coleman’s music. The Frost film won the Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1964, largely I suspect because of Frost’s twinkly personality, undimmed after 88 years. It was an age when films about poets could win Academy Awards and poets could read a poem without it taking longer to explain than it takes to read.

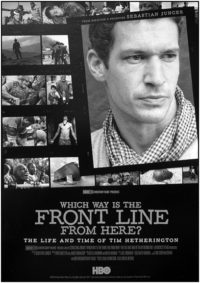

Finally, war reporter Sebastian Junger has made his first film as a solo director and it is a biography of his great collaborator Tim Hetherington. Told with much love, Which Way is the Front Line from Here? is about a man who used his camera to connect with and understand people rather than as a shield or a tool. Hetherington and Junger made the brilliant Restrepo, an Academy Award nominated story of a year in the life of a Marine platoon in Afghanistan. Hetherington, a handsome and laconic Brit, had spent eight years prior to that in West Africa, shooting civil wars, and coming to understand the young man’s need to fight – fighting as a form of expression – and how the powerful exploit that need.

Finally, war reporter Sebastian Junger has made his first film as a solo director and it is a biography of his great collaborator Tim Hetherington. Told with much love, Which Way is the Front Line from Here? is about a man who used his camera to connect with and understand people rather than as a shield or a tool. Hetherington and Junger made the brilliant Restrepo, an Academy Award nominated story of a year in the life of a Marine platoon in Afghanistan. Hetherington, a handsome and laconic Brit, had spent eight years prior to that in West Africa, shooting civil wars, and coming to understand the young man’s need to fight – fighting as a form of expression – and how the powerful exploit that need.

There is so much wisdom and insight in every single one of Hetherington’s photographs featured in the film. I’ll never forget it and, chances are, unless the festival hadn’t handed it to me blind, I would never have seen it. Take a few chances this festival.

I’d like to personally thank NZIFF Publicist, Rebecca McMillan, who for years has put up with my requests for content, access, screeners, interviews, tickets, etc and never once let me believe that I wasn’t the only media that she was dealing with. This year has been particularly hard as I’ve been wrangling four different outlets and she has shown remarkable patience throughout.