Michael Winterbottom somehow manages to make a film a year and, while the quality can go up and down a bit, his work is never less than interesting. He’s most…

Read More

Half way through Winter’s Bone I found myself thinking, “So, this is what the Western has become?” The best Westerns are about finding or sustaining a moral path though a…

Read More

In 1997 two young hotshots stunned the film world by winning an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay for their first produced script. Since then, Matt Damon and Ben Affleck have…

Read More

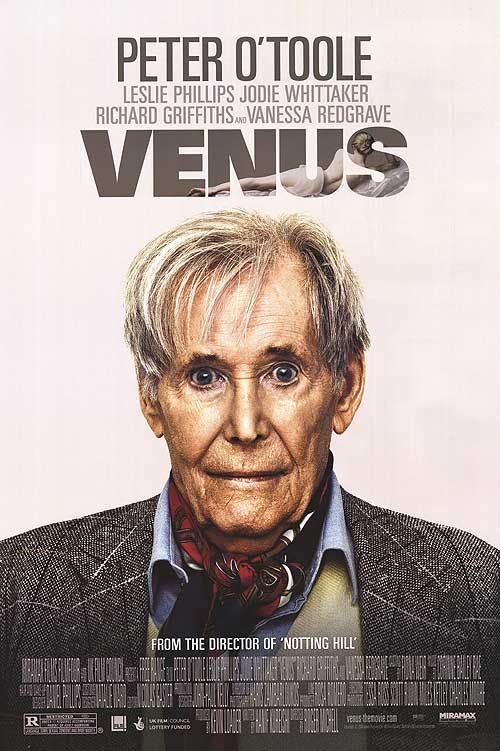

There's something creepy yet disarmingly human about Peter O'Toole's ageing lothario in Venus; a once beautiful actor still working sporadically, his cadaverous features best-suited to the literal portrayal of corpses,…

Read More