In one of these columns back in 2007 I said, “Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be.” Those were the days, eh? Now you can’t get away from it. This…

Read More

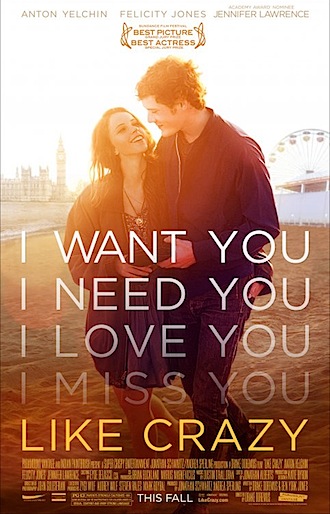

Three films this week point the way towards possible futures for cinema - and if two of them are right then we should all find another hobby. Like Crazy is…

Read More

I’ve been watching reactions to other people’s “Best of 2011” with interest. It’s fascinating to see online commentors insist that films they have seen are so much better than films…

Read More

Here is last night’s show which features discussion of Drive, In Time, One Day, The Inbetweeners Movie and Fright Night:

Read More

Expat Kiwi auteur Andrew Niccol (Gattaca) somehow always manages to tap in to the zeitgeist and with new sci-fi thriller In Time his own timing is almost spookily perfect. A…

Read More