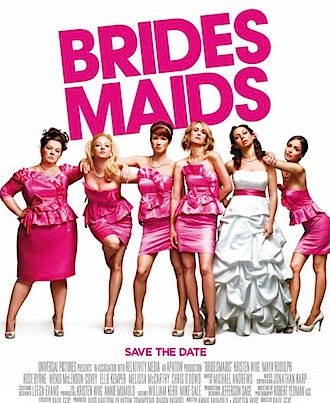

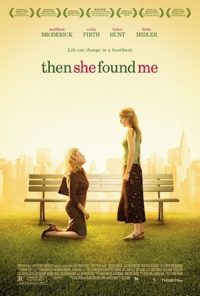

It’s babies everywhere in the cinemas at the moment. Last week I reviewed the Tina Fey comedy Baby Mama about a middle-aged woman desperate for a child and this week we have a Helen Hunt drama about a middle-aged woman desperate for a baby and even Hellboy is going to be a daddy.

Then She Found Me, Helen Hunt’s debut as writer-director, is a sensitive and well-acted piece of work (and often much funnier than the Fey version). She plays a New York primary school teacher whose adoptive mother dies two days after her husband (Matthew Broderick) leaves her. Like many adopted children, the desire for a blood-relative is what promotes the desire for a child, but that desire is soon swamped by the arrival of the birth mother she never knew (Bette Midler) and a ready-made family led by Colin Firth. Witty and humane, Then She Found Me is set in a New York people actually live in, populated with people who actually live and breathe. I was quite moved by this film, but then maybe I’m just a big sook.

Then She Found Me, Helen Hunt’s debut as writer-director, is a sensitive and well-acted piece of work (and often much funnier than the Fey version). She plays a New York primary school teacher whose adoptive mother dies two days after her husband (Matthew Broderick) leaves her. Like many adopted children, the desire for a blood-relative is what promotes the desire for a child, but that desire is soon swamped by the arrival of the birth mother she never knew (Bette Midler) and a ready-made family led by Colin Firth. Witty and humane, Then She Found Me is set in a New York people actually live in, populated with people who actually live and breathe. I was quite moved by this film, but then maybe I’m just a big sook.

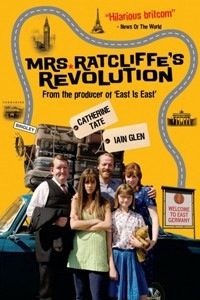

Back in the 1980s, toiling under the yoke of Thatcherite crypto-fascist intolerance, we used to dream of the German Democratic Republic where according to apologists like Billy Bragg, “you can’t get guitar strings but everyone has a job and decent health care.” Now, of course, thanks to films like The Lives of Others, we know that the rulers of East Germany were just fascists with another uniform and that social justice may be important but isn’t the only kind of justice we need in our lives. Mrs Ratcliffe’s Revolution is a low-budget British comedy about a naïve family of Yorkshire communists in 1968 who follow their dreams of a workers’ paradise and emigrate to East Germany only to find the truth very much not to their liking.

Back in the 1980s, toiling under the yoke of Thatcherite crypto-fascist intolerance, we used to dream of the German Democratic Republic where according to apologists like Billy Bragg, “you can’t get guitar strings but everyone has a job and decent health care.” Now, of course, thanks to films like The Lives of Others, we know that the rulers of East Germany were just fascists with another uniform and that social justice may be important but isn’t the only kind of justice we need in our lives. Mrs Ratcliffe’s Revolution is a low-budget British comedy about a naïve family of Yorkshire communists in 1968 who follow their dreams of a workers’ paradise and emigrate to East Germany only to find the truth very much not to their liking.

There might have been an interesting story here buried under the broad comedy – sometimes it seems like Carry on Communism – but the tone is all wrong and it feels as if it has gone intellectually off the rails. There’s some nice architecture although the filmmakers had to go to Hungary to find it.

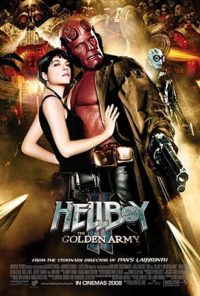

Sometimes, when you go to the movies, you get the perfect match of film to mood. Not often, but sometimes. Last Friday night, after a week where the ambient stress level at work had amped up yet again, I needed to see something that didn’t require anything of me except my presence and I got it with Hellboy II: The Golden Army. Featuring lots of bright shiny things to keep my attention, lots of loud noises to keep me awake and not much in the way of story to worry about, I enjoyed myself a lot but don’t remember very much. Except noting that, unlike The Dark Knight’s Christopher Nolan, director Guillermo Del Toro (Pan’s Labyrinth and the forthcoming Hobbit duo-logy) shoots fight scenes so you can follow what’s going on.

Sometimes, when you go to the movies, you get the perfect match of film to mood. Not often, but sometimes. Last Friday night, after a week where the ambient stress level at work had amped up yet again, I needed to see something that didn’t require anything of me except my presence and I got it with Hellboy II: The Golden Army. Featuring lots of bright shiny things to keep my attention, lots of loud noises to keep me awake and not much in the way of story to worry about, I enjoyed myself a lot but don’t remember very much. Except noting that, unlike The Dark Knight’s Christopher Nolan, director Guillermo Del Toro (Pan’s Labyrinth and the forthcoming Hobbit duo-logy) shoots fight scenes so you can follow what’s going on.

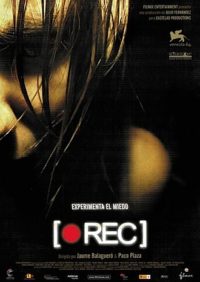

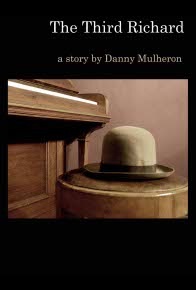

The Paramount’s eclectic (if not schizophrenic) programming policy throws up some odd combinations. The presence of the hideous, animated, Bible-story The Ten Commandments is simply inexplicable while Spanish shocker [REC] is perfect Paramount fodder. And at the same time, Danny Mulheron’s loving home-made documentary about his grandfather, The Third Richard, is getting a well-deserved brief season. The Ten Commandments barely belongs in the $5 DVD bargain-bin (or as a free gift when you sign up with your local evangelicals). It’s a sign of how our culture has changed that in the 50s we got Charlton Heston bringing the tablets down from the mountain, and now we get Christian Slater. And what to make of the subtle re-writing of the commandments themselves: Thou Shalt Not Murder gives you a little more wiggle-room in the killing department than the old-fashioned Thou Shalt Not Kill. Reprehensible.

The Paramount’s eclectic (if not schizophrenic) programming policy throws up some odd combinations. The presence of the hideous, animated, Bible-story The Ten Commandments is simply inexplicable while Spanish shocker [REC] is perfect Paramount fodder. And at the same time, Danny Mulheron’s loving home-made documentary about his grandfather, The Third Richard, is getting a well-deserved brief season. The Ten Commandments barely belongs in the $5 DVD bargain-bin (or as a free gift when you sign up with your local evangelicals). It’s a sign of how our culture has changed that in the 50s we got Charlton Heston bringing the tablets down from the mountain, and now we get Christian Slater. And what to make of the subtle re-writing of the commandments themselves: Thou Shalt Not Murder gives you a little more wiggle-room in the killing department than the old-fashioned Thou Shalt Not Kill. Reprehensible.

One is either in to zombie movies or one isn’t, and if one is one will be very happy with [REC]. Set in a Barcelona apartment building where a fly-on-the-wall tv crew are following fire-fighters on an emergency call, [REC] at one point managed to make me jump three times in less than a second – that’s not easy.

One is either in to zombie movies or one isn’t, and if one is one will be very happy with [REC]. Set in a Barcelona apartment building where a fly-on-the-wall tv crew are following fire-fighters on an emergency call, [REC] at one point managed to make me jump three times in less than a second – that’s not easy.

The story of Richard Fuchs, architect and composer, emigré and grandfather, is very well told by Danny Mulheron and Sara Stretton. Based around a “rehabilitation” concert in Karlsruhe, last year, where Fuchs’ music was played in public for the first time since his escape to New Zealand in 1939, the film has some stylistic choices that I might not have made but the heart and intelligence of the filmmmakers shine through. It’s a Wellington story, too, and you should see it if you can.

The story of Richard Fuchs, architect and composer, emigré and grandfather, is very well told by Danny Mulheron and Sara Stretton. Based around a “rehabilitation” concert in Karlsruhe, last year, where Fuchs’ music was played in public for the first time since his escape to New Zealand in 1939, the film has some stylistic choices that I might not have made but the heart and intelligence of the filmmmakers shine through. It’s a Wellington story, too, and you should see it if you can.

Printed in Wellington’s Capital Times on Wednesday 3 September, 2008.

Notes on screening conditions: Mrs Ratcliffe’s Revolution was interrupted twice by the house lights (a Sunday morning screening in Penthouse 2, still suffering from the annoying screen flicker caused by incorrect shutter timing and the hot spot in the centre of the screen). And I had to go down and close the door at the start of the film. At [REC] quite a few of us were sat in the Brooks (Paramount) amidst the bottles, empty glasses and general rubbish from a whole day’s screenings. <Sigh>

![Review: Then She Found Me, Hellboy II: The Golden Army, Mrs. Ratcliffe’s Revolution, The Ten Commandments, [REC] and The Third Richard](https://funeralsandsnakes.net/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/200809061657.jpg)