In October 1975, the obscure little Portuguese colony of East Timor was given independence after 400 years of European rule. A mixed Melanesian/Polynesian population was sitting on rich mineral and fossil fuel potential and surrounded on three sides by the region’s powerhouse, Indonesia (with Australia to the south). After only nine days of independence, Indonesia invaded in one of the most cynical and brutal land grabs in modern history.

In October 1975, the obscure little Portuguese colony of East Timor was given independence after 400 years of European rule. A mixed Melanesian/Polynesian population was sitting on rich mineral and fossil fuel potential and surrounded on three sides by the region’s powerhouse, Indonesia (with Australia to the south). After only nine days of independence, Indonesia invaded in one of the most cynical and brutal land grabs in modern history.

The Indonesian armed forces, knowing that an invasion was a gross breach of international law, wore plain clothes and did everything they could to extinguish evidence and witnesses. The most celebrated victims of the atrocity were the Balibo 5, young Australian television journalists who were stranded in the border town of Balibo as the invasion began. Without the benefit of modern-day communications, they simply disappeared and the Australian government, who (along with the US) gave tacit approval to the entire horrible exercise.

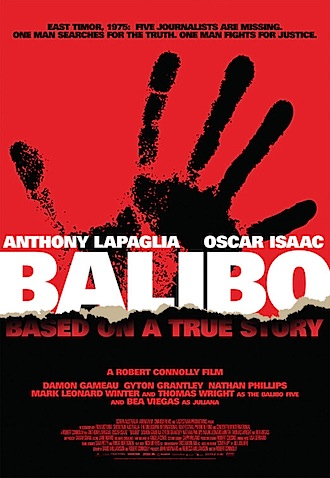

Balibo, the feature film, is the story of the Balibo 5 told through the eyes of former crusading journalist (now on the skids) Roger East, played by Anthony LaPaglia. East arrives in Dili just before the invasion (the Balibo 5 disappeared while the Indonesians were still indulging in terrifying border skirmishes) and, with the help of Timorese leader (now President) José Ramos-Horta he searches for the truth until the Indonesians stop him, too, from telling the world what happened.

The Balibo atrocity, and the Indonesian invasion of Timor, gets a suitably powerful cinematic portrayal in Robert Connolly’s excellent film and heavyweight LaPaglia has never been better as the conscience-stricken hack who becomes the only link to the outside world. If I had any tiny criticism it might be that the film skates around the complicity of the Australian government in the deaths of the journalists (there is one brief suggestion that Australia actually alerted the Indonesians to their presence), but for the most part Balibo is essential viewing – passionate and moving.

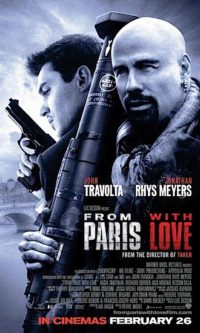

Luc Besson has made a good living churning out high energy European B movies (mostly dumb, like The Transporter, occasionally excellent, like Taken) but he must have run out of napkins to write From Paris with Love on because it is really very thin indeed. Simpering Jonathan Rhys Meyers plays a US diplomat in Paris, moonlighting for the CIA. He gets a sudden promotion when wildcard secret agent John Travolta comes to town and needs a minder. Travolta chews any and all scenery he can get his hands on and is completely out of the control of director Pierre Morel who had better luck with disciplined Liam Neeson in Taken last year.

Luc Besson has made a good living churning out high energy European B movies (mostly dumb, like The Transporter, occasionally excellent, like Taken) but he must have run out of napkins to write From Paris with Love on because it is really very thin indeed. Simpering Jonathan Rhys Meyers plays a US diplomat in Paris, moonlighting for the CIA. He gets a sudden promotion when wildcard secret agent John Travolta comes to town and needs a minder. Travolta chews any and all scenery he can get his hands on and is completely out of the control of director Pierre Morel who had better luck with disciplined Liam Neeson in Taken last year.

Due to a wardrobe malfunction on my part I had to watch this film through my (prescription) sunglasses. Frankly, I would have preferred something even more opaque, like a shower curtain or the wall of the cinema next door while it played a completely different film.

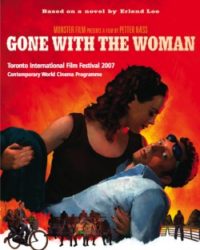

Gone With the Woman is a deeply unfunny comedy from Norway about a young man whose life is turned upside down by the arrival of a high-spirited young lady in his life. With the help of some wise old geezers at the local sauna he tries to cope with her eccentricities, inconsistencies and her deeply annoying, and at the same time, completely unrealistic, behaviours. Borderline misogynistic at best and directed like an expensive Heineken tv commercial spun out to an hour and a half, I have to say it did look quite handsome on the Paramount’s new hi-def digital projector (even if they hadn’t bothered to get the ratio exactly right).

Gone With the Woman is a deeply unfunny comedy from Norway about a young man whose life is turned upside down by the arrival of a high-spirited young lady in his life. With the help of some wise old geezers at the local sauna he tries to cope with her eccentricities, inconsistencies and her deeply annoying, and at the same time, completely unrealistic, behaviours. Borderline misogynistic at best and directed like an expensive Heineken tv commercial spun out to an hour and a half, I have to say it did look quite handsome on the Paramount’s new hi-def digital projector (even if they hadn’t bothered to get the ratio exactly right).

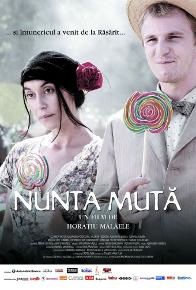

I’m not sure what to say about the peculiar Silent Wedding, a Romanian comedy set in the 1950s. The bucolic rural existence of a village full of “characters” is upset when the death of Stalin almost puts a stop to a big village wedding. Instead of cancelling they decide to hold the wedding in silence (hence the title) which leads to an amusing central set-piece that Chaplin might have constructed. My problem was that they were all so boisterous and noisy (and broad in the acting sense) in the first half that I couldn’t wait for them to shut up which I don’t think was the point.

I’m not sure what to say about the peculiar Silent Wedding, a Romanian comedy set in the 1950s. The bucolic rural existence of a village full of “characters” is upset when the death of Stalin almost puts a stop to a big village wedding. Instead of cancelling they decide to hold the wedding in silence (hence the title) which leads to an amusing central set-piece that Chaplin might have constructed. My problem was that they were all so boisterous and noisy (and broad in the acting sense) in the first half that I couldn’t wait for them to shut up which I don’t think was the point.

It being Romanian, the comedy is blacker than pitch and is bookended by a grim, grey modern scene intended to contrast with the golden summer tones of the main story. I thought it was all a bit heavy-handed to be honest.

My New Year’s resolution is to go to more than one screening at the Film Society this year. I love the Society and its year round commitment to film art and they have responded to some criticism of last year’s programme with a resurgence in celluloid over DVD – not the least of which is a 35mm presentation of Billy Wilder’s timeless classic Some Like It Hot (courtesy of the MGM Channel).

There are the usual fascinating programmes supplied by the French Government and the Goethe Institute from Germany, a series of films from Iran including the wonderful The White Balloon (although no Crimson Gold, my favourite Iranian film of the last decade), Tarkovsky’s great masterpiece Stalker plus Astaire and Rogers in Swing Time. I have to wait until November for my personal highlight: Bogart and Bacall together for the first time in To Have and Have Not, one of the great celluloid romances and twice the film that Casablanca ever was. “You know how to whistle, don’t you? You just put your lips together and blow.” Heaven.

Printed in Wellington’s Capital Times on Wednesday 3 March, 2010.

Added bonus: Here is that famous line delivered by the gorgeous Bacall when she was only 19.