Of all the massively successful franchise conversions from best-selling-books-that-I-haven’t‑read, I’m pleased to say that I like this Hunger Games film the best. I’ve been justifiably scornful of the Harry Potter films in these pages and downright disdainful of Twilight but – while still not reaching out much to me personally – I can say that Hunger Games actually succeeds much more on its own cinematic terms.

Of all the massively successful franchise conversions from best-selling-books-that-I-haven’t‑read, I’m pleased to say that I like this Hunger Games film the best. I’ve been justifiably scornful of the Harry Potter films in these pages and downright disdainful of Twilight but – while still not reaching out much to me personally – I can say that Hunger Games actually succeeds much more on its own cinematic terms.

Jennifer Lawrence basically repeats her Academy Award-nominated turn from Winter’s Bone as a plucky Appalachian teen forced to risk everything to protect her young sister while her traumatised mother remains basically useless. In this film, though, the enemy isn’t toothless meth dealers but the full force of a fascist state where the 99% is enslaved in various “districts” and forced to produce whatever the decadent 1% back in Capitol City require in order to keep them in their Klaus Nomi-inspired makeup and hair.

To make matters worse the Capitol also uses the plebs for entertainment, selecting teens from each district for a televised battle-to-the-death. Lawrence’s character – I keep wanting to call her Catnip Everclear but I’m not sure that’s right – volunteers for the tournament when her younger sister’s name is drawn from tombola. Trained by Woody Harrelson and styled by Lenny Kravitz she becomes – despite her down-home country roots – a crowd favourite which only means the odds get stacked against her.

I like the fact that there isn’t a supernatural aspect to this blockbuster – Lawrence uses genuine hunting skills to survive and the sense of jeopardy throughout is palpable. While I wish director Gary Ross (Seabiscuit) wouldn’t wobble the camera about quite so much, I’m still keen to see where the next two episodes of this story go.

In The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel – a license to print money in the New Zealand market if there ever was one – a group of elderly Brits choose a Jaipuri retirement home they found on the internet rather than withering away in Blighty. Each of them has their own story, of course, and each arc plays itself out in satisfying fashion. The top-notch cast – including Judi Dench, Bill Nighy, Maggie Smith and a surprisingly easy-going Tom Wilkinson – make it all look easy. All of the characters – British and Indian – tiptoe into stereotype territory without becoming downright offensive and the various conclusions are quite affecting. The most helpful thing I can say about it is, if you think you are likely to enjoy it you certainly will.

In The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel – a license to print money in the New Zealand market if there ever was one – a group of elderly Brits choose a Jaipuri retirement home they found on the internet rather than withering away in Blighty. Each of them has their own story, of course, and each arc plays itself out in satisfying fashion. The top-notch cast – including Judi Dench, Bill Nighy, Maggie Smith and a surprisingly easy-going Tom Wilkinson – make it all look easy. All of the characters – British and Indian – tiptoe into stereotype territory without becoming downright offensive and the various conclusions are quite affecting. The most helpful thing I can say about it is, if you think you are likely to enjoy it you certainly will.

In The Hunter, Willem Dafoe plays a mysterious dude commissioned by a multinational drug company to find the last Tasmanian Tiger. His secret mission takes him into the wilderness, above the battle between conservationists and loggers over native forest, but he’s not the only one after the supposedly extinct – and frankly bizarre – animal. Extremely well made, tense as all get out, only let down by an ending that tries to tie up every single loose end when it doesn’t have to, The Hunter is easy to miss but worth seeking out.

In The Hunter, Willem Dafoe plays a mysterious dude commissioned by a multinational drug company to find the last Tasmanian Tiger. His secret mission takes him into the wilderness, above the battle between conservationists and loggers over native forest, but he’s not the only one after the supposedly extinct – and frankly bizarre – animal. Extremely well made, tense as all get out, only let down by an ending that tries to tie up every single loose end when it doesn’t have to, The Hunter is easy to miss but worth seeking out.

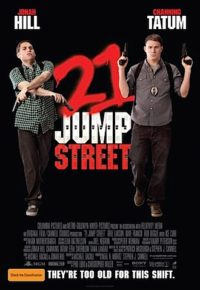

21 Jump Street is a jolly but forgettable romp using the old TV series as jumping off point for a by-the-numbers R‑rated comedy that actually has a few jokes in it. The other notable aspect of the picture is that I’m starting to see the potential in Channing Tatum. As his partner, Jonah Hill’s range is not so extended.

21 Jump Street is a jolly but forgettable romp using the old TV series as jumping off point for a by-the-numbers R‑rated comedy that actually has a few jokes in it. The other notable aspect of the picture is that I’m starting to see the potential in Channing Tatum. As his partner, Jonah Hill’s range is not so extended.

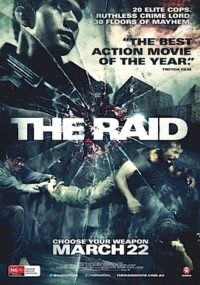

Storming out of – not quite – nowhere, Gareth Evans’ The Raid is a stunning example of pure cinema – action, editing, sound design and choreography all harnessed to a beautifully simple story that once kicked-off, doesn’t let go. An Indonesian SWAT team are sent to capture a big time – but untouchable – drug dealer from his lair at the top of a run-down apartment building defended by hordes of expendable henchmen. Yes, it’s violent but there’s a purity about its expression that makes it quite beautiful. If you replaced the impact sound effects with music, The Raid becomes intense and powerful contemporary dance.

Storming out of – not quite – nowhere, Gareth Evans’ The Raid is a stunning example of pure cinema – action, editing, sound design and choreography all harnessed to a beautifully simple story that once kicked-off, doesn’t let go. An Indonesian SWAT team are sent to capture a big time – but untouchable – drug dealer from his lair at the top of a run-down apartment building defended by hordes of expendable henchmen. Yes, it’s violent but there’s a purity about its expression that makes it quite beautiful. If you replaced the impact sound effects with music, The Raid becomes intense and powerful contemporary dance.

At the beginning of In Search of Haydn, narrator Juliet Stevenson makes the bold assertion that the great composer was at least the equal of contemporaries Mozart and Beethoven. Phil Grabsky’s film – the third in a series of “In Search of” films – then proceeds at some length to fail to make that case. It features lots of damning with faint praise from the assembled musical experts – soprano Sophie Bevan talks about how easy Haydn arias are to sing but how difficult they are to make beautiful, for example – and the extended examples from the repertoire don’t quite set the heart a‑flutter. The other problem Grabsky fails to wrestle with is the fundamentally undramatic life old Haydn lived – long, productive, successful and happy. Who wants to see that?

At the beginning of In Search of Haydn, narrator Juliet Stevenson makes the bold assertion that the great composer was at least the equal of contemporaries Mozart and Beethoven. Phil Grabsky’s film – the third in a series of “In Search of” films – then proceeds at some length to fail to make that case. It features lots of damning with faint praise from the assembled musical experts – soprano Sophie Bevan talks about how easy Haydn arias are to sing but how difficult they are to make beautiful, for example – and the extended examples from the repertoire don’t quite set the heart a‑flutter. The other problem Grabsky fails to wrestle with is the fundamentally undramatic life old Haydn lived – long, productive, successful and happy. Who wants to see that?

Printed in Wellington’s Capital Times on Wednesday 28 March, 2012.