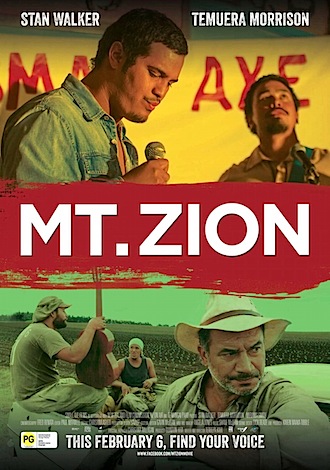

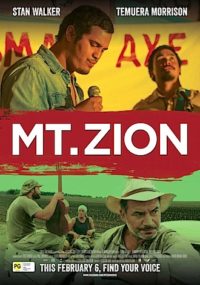

Kiwi crowd-pleasers don’t come much more crowd-pleasing than Tearepa Kahi’s Mt. Zion, featuring TV talent quester Stan Walker in a star-making performance as a working class kid with a dream. Slogging his unwilling guts out picking potatoes in the market gardens of 1979 Pukekohe, nervously making the first steps in a music career that seems impossible and fantasising about meeting the great Bob Marley, Walker’s Turei is out of step with his hard working father (Temuera Morrison) and the back-breaking work.

Kiwi crowd-pleasers don’t come much more crowd-pleasing than Tearepa Kahi’s Mt. Zion, featuring TV talent quester Stan Walker in a star-making performance as a working class kid with a dream. Slogging his unwilling guts out picking potatoes in the market gardens of 1979 Pukekohe, nervously making the first steps in a music career that seems impossible and fantasising about meeting the great Bob Marley, Walker’s Turei is out of step with his hard working father (Temuera Morrison) and the back-breaking work.

When a local promoter announces a competition to be the support act for the reggae legend’s forthcoming concert at Western Springs, Turei tests the boundaries of family and friendship to get a shot at the big time. The bones of the story are familiar, of course, but there’s meat on the bones too – a slice of New Zealand social history with economic changes making life harder for a people who don’t own the land that they work. Production design (by Savage) and authentic-looking 16mm photography all help give Mt. Zion a look of its own and the music – though not normally to my taste – is agreeable enough.

Sacha Gervasi’s Hitchcock presents the great director as a petulant child, a combination of immature pathologies rather than the extraordinary technician that he actually was. The film opens with the première of the masterpiece North by Northwest when – in a clunky bit of exposition typical of John J. McLaughlin’s script – a reporter asks the 60 year old filmmaker whether he’s past it and should quit while he’s ahead. What follows is the story of the making of Psycho, a film that redefined Hitchcock’s reputation and virtually invented the independent financing of studio movies.

Sacha Gervasi’s Hitchcock presents the great director as a petulant child, a combination of immature pathologies rather than the extraordinary technician that he actually was. The film opens with the première of the masterpiece North by Northwest when – in a clunky bit of exposition typical of John J. McLaughlin’s script – a reporter asks the 60 year old filmmaker whether he’s past it and should quit while he’s ahead. What follows is the story of the making of Psycho, a film that redefined Hitchcock’s reputation and virtually invented the independent financing of studio movies.

There’s a lot of fluff around this story to match the psychological invention – wife Alma Reville’s lack of recognition (Helen Mirren), Hitchcock’s pedestal-ising of those blondes he was so famous for, etc. – but none of it feels terribly legitimate, much like Anthony Hopkins’ prosthetically-aided impersonation of the great master.

Throughout the film, Hitchcock complains that he wants to try something new, be more adventurous, break out. After watching (one) Farrelly Brother’s “experimental” Movie 43 I can safely say that novelty ain’t always such a good thing. It’s a collection of filthy sketches featuring stars like Kate Winslet – I hesitate to say “debasing” themselves but there’s really no polite way to put it – loosely linked by wild-eyed Dennis Qaid pitching to a straight Hollywood executive played by Greg Kinnear. If you’ve ever yearned to see Hugh Jackman walking around with a pair of testicles hanging from his chin, this is the film for you – except if it wasn’t screened in a cinema and projected through actual film, I wouldn’t call it a film at all.

Throughout the film, Hitchcock complains that he wants to try something new, be more adventurous, break out. After watching (one) Farrelly Brother’s “experimental” Movie 43 I can safely say that novelty ain’t always such a good thing. It’s a collection of filthy sketches featuring stars like Kate Winslet – I hesitate to say “debasing” themselves but there’s really no polite way to put it – loosely linked by wild-eyed Dennis Qaid pitching to a straight Hollywood executive played by Greg Kinnear. If you’ve ever yearned to see Hugh Jackman walking around with a pair of testicles hanging from his chin, this is the film for you – except if it wasn’t screened in a cinema and projected through actual film, I wouldn’t call it a film at all.

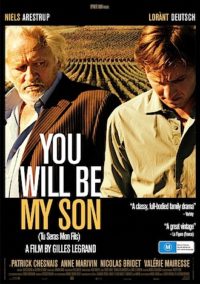

A brief word about a couple of French movies featuring tensions between fathers and sons in the food and beverage business – one is an over-egged melodrama about the wine business called You Will Be My Son and the other is one of those foodie documentaries, the awfully named Step Up to the Plate. In Son, patriarch (Niels Arestrup) decides to hand over his operation to the son of his winemaker rather than his own child but it never takes flight. Plate features the multi-Michelined Michel Bras as he prepares to handover his Aveyron empire to his son Sébastian. Will Sébastian measure up is the question posed and I suspect the tension is exaggerated a little by the filmmakers. Not as much food in this one as you might think.

A brief word about a couple of French movies featuring tensions between fathers and sons in the food and beverage business – one is an over-egged melodrama about the wine business called You Will Be My Son and the other is one of those foodie documentaries, the awfully named Step Up to the Plate. In Son, patriarch (Niels Arestrup) decides to hand over his operation to the son of his winemaker rather than his own child but it never takes flight. Plate features the multi-Michelined Michel Bras as he prepares to handover his Aveyron empire to his son Sébastian. Will Sébastian measure up is the question posed and I suspect the tension is exaggerated a little by the filmmakers. Not as much food in this one as you might think.

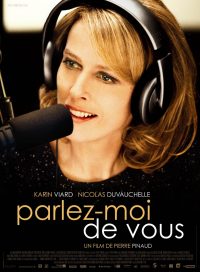

In On Air, Karin Viard plays that great cliché – the agony aunt whose own life needs plenty of sorting out – and adds very little to it. The twist in this case would be the extremes of her success and failure. She is a top-rating star on French night time radio – anonymity adding to her mystery – but in her austere apartment she sleeps in a closet instead of the bedroom because she is still traumatised about being abandoned to an orphanage as a child. Locating her mother in a Paris suburb she goes seeking resolution but instead gets involved in her new family in ways that amplify her own tragedy. I know that this stuff happens in real life but something about the execution here – more melodrama? – meant I didn’t buy it for a minute.

In On Air, Karin Viard plays that great cliché – the agony aunt whose own life needs plenty of sorting out – and adds very little to it. The twist in this case would be the extremes of her success and failure. She is a top-rating star on French night time radio – anonymity adding to her mystery – but in her austere apartment she sleeps in a closet instead of the bedroom because she is still traumatised about being abandoned to an orphanage as a child. Locating her mother in a Paris suburb she goes seeking resolution but instead gets involved in her new family in ways that amplify her own tragedy. I know that this stuff happens in real life but something about the execution here – more melodrama? – meant I didn’t buy it for a minute.

Also struggling with authenticity, Robert Zemeckis’ Flight starts out with an air disaster almost as harrowing as The Impossible’s tsunami, but then turns into a kitchen sink drama about one man’s battle with the bottle. Denzel Washington plays against type as the troubled pilot who saves a plane load of passengers while stoned off his gourd and Don Cheadle is the lawyer trying to keep him out of jail. Avoiding the awkward fact that most regional pilots in the US are so badly paid that they have to pull double-shifts and extra jobs just to make ends meet – that’s your major safety risk, right there – Flight is about one man’s demons and has a few cute narrative tricks up its sleeve.

Also struggling with authenticity, Robert Zemeckis’ Flight starts out with an air disaster almost as harrowing as The Impossible’s tsunami, but then turns into a kitchen sink drama about one man’s battle with the bottle. Denzel Washington plays against type as the troubled pilot who saves a plane load of passengers while stoned off his gourd and Don Cheadle is the lawyer trying to keep him out of jail. Avoiding the awkward fact that most regional pilots in the US are so badly paid that they have to pull double-shifts and extra jobs just to make ends meet – that’s your major safety risk, right there – Flight is about one man’s demons and has a few cute narrative tricks up its sleeve.

Washington does a lot of drunk acting and a lot of hungover acting, rarely unleashing that movie star smile. Last time we saw him he was driving a train in Unstoppable. Maybe that third Oscar will finally come when he hits the transportation trifecta and plays a Wellington trolley-bus driver. They should call it Snapper.

Printed in Wellington’s Capital Times on 13 February, 2013.

Update: As was pointed out to me shortly after this column went to print, I had completely forgotten Mr. Washington’s previous film was Safe House, a fact which ruins that last paragraph joke.