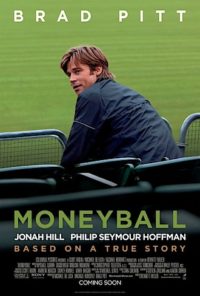

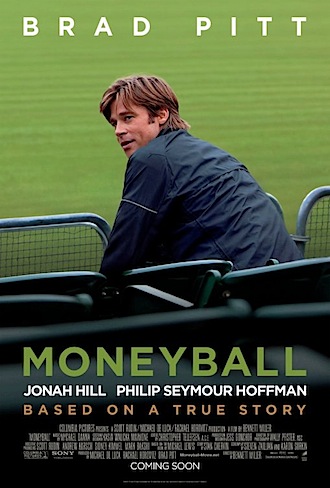

This week Philip Seymour Hoffman features in two new American sports movies, one about their most venerable – if not impenetrable – pastime of baseball and the other on the modern-day equivalent of bear-baiting, the presidential primaries. In Moneyball, Hoffman plays Art, team manager of the Oakland Athletics, left behind when his boss – Brad Pitt – decides to throw away decades of baseball tradition and use sophisticated statistical analysis and a schlubby Yale economics graduate (Jonah Hill) to pick cheap but effective players.

This week Philip Seymour Hoffman features in two new American sports movies, one about their most venerable – if not impenetrable – pastime of baseball and the other on the modern-day equivalent of bear-baiting, the presidential primaries. In Moneyball, Hoffman plays Art, team manager of the Oakland Athletics, left behind when his boss – Brad Pitt – decides to throw away decades of baseball tradition and use sophisticated statistical analysis and a schlubby Yale economics graduate (Jonah Hill) to pick cheap but effective players.

Hoffman steals every scene he is in but disappears from the story too early. Having said that, Pitt and Hill do great work underplaying recognisably real people and all are well-supported by Steve Zaillian and Aaron Sorkin’s script which has scene after scene of great moments, even if some of them lead nowhere (like poor Art’s arc). Moneyball might start out a sports movie but it’s actually a business textbook. If the place you work at clings to received wisdom, experience and intuition over “facts” then organise an outing to Moneyball as fast as you can.

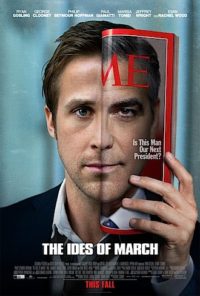

Hoffman then proceeds to act the great Ryan Gosling off the screen in every scene they share in The Ides of March, George Clooney’s latest as director. It’s coming up to the crucial Ohio primary and Clooney’s idealistic state governor Morris needs a tiny push to confirm the nomination against his more traditional opponent. Hoffman is seasoned campaign manager Paul Zara and Gosling is the gifted young apprentice. When the wheels start to fall off – mostly self-inflicted by a campaign that doesn’t know whether it prefers winning to being right – they turn on each other and the veneer of idealism disintegrates.

Hoffman then proceeds to act the great Ryan Gosling off the screen in every scene they share in The Ides of March, George Clooney’s latest as director. It’s coming up to the crucial Ohio primary and Clooney’s idealistic state governor Morris needs a tiny push to confirm the nomination against his more traditional opponent. Hoffman is seasoned campaign manager Paul Zara and Gosling is the gifted young apprentice. When the wheels start to fall off – mostly self-inflicted by a campaign that doesn’t know whether it prefers winning to being right – they turn on each other and the veneer of idealism disintegrates.

I’m still not sure whether Gosling is genuinely out his depth in The Ides of March or is just playing someone who is. Even so, Clooney’s film is strangely cynical about political motivation but would have been much more entertaining if he’d focused on the clowns currently fighting it out on the Republican side.

Steve McQueen’s Shame may be the best portrait of addiction and trauma ever committed to the screen, a harrowing yet riveting story of two siblings failing to deal with some unspecificied childhood trauma in different but equally self-destructive ways. Michael Fassbender plays Brandon: a successful career in Manhattan hides his addiction to sex, an addicition that prevents him from forming relationships or even staying too long in his own head. Meanwhile sister Sissy (Carey Mulligan) goes from one dependant relationship to another, masking her own unhappiness.

Steve McQueen’s Shame may be the best portrait of addiction and trauma ever committed to the screen, a harrowing yet riveting story of two siblings failing to deal with some unspecificied childhood trauma in different but equally self-destructive ways. Michael Fassbender plays Brandon: a successful career in Manhattan hides his addiction to sex, an addicition that prevents him from forming relationships or even staying too long in his own head. Meanwhile sister Sissy (Carey Mulligan) goes from one dependant relationship to another, masking her own unhappiness.

What could be – and let’s face it, is – a troubling subject to watch is softened by McQueen’s beautiful eye and even though he and co-screenwriter Abi Morgan occasionally overplay their hand with the visual allusions the film itself is never less than ravishing. Shame is one of the most important films of recent years and it thoroughly recommended.

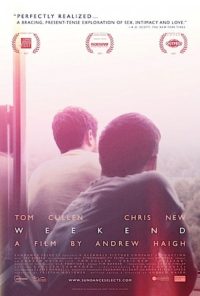

Another side of the same coin – and equally mandatory viewing – is the ultra-low budget Brit indie Weekend. Two gay men meet at a bar and have a one-night stand but it doesn’t take too long before they realise that something deeper has been stimulated and they simply have to see each other again. Which would be great – except one of them only has the weekend before he leaves the country for two years. What connections can (or should) they make in only two days?

Another side of the same coin – and equally mandatory viewing – is the ultra-low budget Brit indie Weekend. Two gay men meet at a bar and have a one-night stand but it doesn’t take too long before they realise that something deeper has been stimulated and they simply have to see each other again. Which would be great – except one of them only has the weekend before he leaves the country for two years. What connections can (or should) they make in only two days?

Weekend is a beautiful portrayal of the dance that is the first stage of a relationship, when intimacy – of the kind that Fassbender’s Brandon is so unable to experience in Shame – is that potent mix of terrifying and transformative.

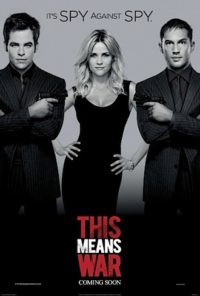

Last week Valentine’s Day went unremarked in this house apart from watching the films that were released to exploit it. This Means War is about two young men competing for the same girl (Reese Witherspoon) and treats the lying, cheating, spying and double-dealing that results as simply all fair in love and war. Speaking as someone who has never knowingly under-prepared for a date, I can understand the impulses at the core of This Means War but what I can’t forgive is the bone-headed execution from director McG (Charlie’s Angels) and the utter charmlessness of the two leads (Star Trek’s Chris Pine and usually brilliant young Brit Tom Hardy).

Last week Valentine’s Day went unremarked in this house apart from watching the films that were released to exploit it. This Means War is about two young men competing for the same girl (Reese Witherspoon) and treats the lying, cheating, spying and double-dealing that results as simply all fair in love and war. Speaking as someone who has never knowingly under-prepared for a date, I can understand the impulses at the core of This Means War but what I can’t forgive is the bone-headed execution from director McG (Charlie’s Angels) and the utter charmlessness of the two leads (Star Trek’s Chris Pine and usually brilliant young Brit Tom Hardy).

The French entry in the “make Valentine’s Day go away” competition is Romantics Anonymous, a comedy about two shy people working together in a chocolate factory who – for no apparant reason – fall instantly in love and then fail to do anything about it. Bearing no resemblance to real life whatsoever, Romantics Anonymous will prove to be a waste of time for most of you.

The French entry in the “make Valentine’s Day go away” competition is Romantics Anonymous, a comedy about two shy people working together in a chocolate factory who – for no apparant reason – fall instantly in love and then fail to do anything about it. Bearing no resemblance to real life whatsoever, Romantics Anonymous will prove to be a waste of time for most of you.

Regular readers will know that I have a soft spot for animal redemption movies (Dolphin Tale, Secretariat) but Big Miracle won me over with more than just the true story of a famous 1988 Alaskan whale rescue. In a very tidy 107 minutes it manages to cover lots of ground smartly and sensitively – indigenous rights and culture; the tension between economic development and environmental preservation, regional politics versus national politics and the end of the Cold War.

Regular readers will know that I have a soft spot for animal redemption movies (Dolphin Tale, Secretariat) but Big Miracle won me over with more than just the true story of a famous 1988 Alaskan whale rescue. In a very tidy 107 minutes it manages to cover lots of ground smartly and sensitively – indigenous rights and culture; the tension between economic development and environmental preservation, regional politics versus national politics and the end of the Cold War.

Big Miracle is a film with plenty of antagonists but no villain – even Drew Barrymore’s heroic Greenpeace activist turns out to be more stubborn and inflexible than Ted Danson’s oil executive – and one of the more bizarre conclusions to the story even turns out to be true with the wedding photos over the closing credits to prove it. Big Miracle is a good, positive, cockle-warming film and is well worth a family trip to the pictures.

Printed in Wellington’s Capital Times on Wednesday 22 February, 2012.

Like it Dan as always – Graeme Tuckett on National Radio didn’t like Shame one little bit. I sense if you’ve come from, or had a close experience with addiction, your appreciation of this film may be deeper. Good stuff mate.

Thanks Perky. It may have been too close to home for GT, who knows? It’s such a troublesome area. I found it hard to discuss without relating it back to my own experience.