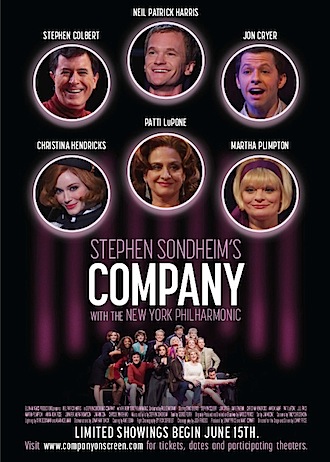

The most pleasure I have had in a cinema so far this year wasn’t at a film. In 2011, the New York Philharmonic produced a brief concert revival of Stephen Sondheim’s masterpiece about emotional opportunity cost, Company. For three performances only, they assembled a star-studded cast of well-known television faces including Stephen Colbert, Jon Cryer and Mad Men’s Christina Hendricks, alongside Broadway veterans like Patti LuPone, and the show was filmed in high-definition for distribution to cinemas around the world. Several Wellington picture houses are playing this sort of alternative content these days – the Metropolitan Opera etc – so, eventually, this stunning production was likely to arrive here and, golly, I am so glad it did.

The most pleasure I have had in a cinema so far this year wasn’t at a film. In 2011, the New York Philharmonic produced a brief concert revival of Stephen Sondheim’s masterpiece about emotional opportunity cost, Company. For three performances only, they assembled a star-studded cast of well-known television faces including Stephen Colbert, Jon Cryer and Mad Men’s Christina Hendricks, alongside Broadway veterans like Patti LuPone, and the show was filmed in high-definition for distribution to cinemas around the world. Several Wellington picture houses are playing this sort of alternative content these days – the Metropolitan Opera etc – so, eventually, this stunning production was likely to arrive here and, golly, I am so glad it did.

In Company, Neil Patrick Harris (How I Met Your Mother) plays Robert – a 35 year old confirmed New York bachelor surrounded by married and soon-to-be-married friends. Throughout the show they give him some good, bad and indifferent advice about the importance of relationships versus freedom and independence versus – well – company. This is a concert production so the orchestra is on the stage rather than tucked away in a pit, and director Lonny Price does marvels with the shallow area that remains. Transitions are inventive and smooth and the characters somehow manage to relate to each other despite being – as Sondheim would have it – side by side.

But it’s the music and lyrics that triumph in this production, showcasing Sondheim’s genius for wordplay and character. I found myself shedding tears of happiness several times, and when Harris followed LuPone’s showstopping – devastating – Ladies Who Lunch with the glorious Being Alive you really feel ten times more alive yourself.

If you’re one of those people who for one reason or another doesn’t go to theatre, you could do worse than trying Company, or one of the brilliant NTLive productions beamed in from the National Theatre on London’s South Bank. Unlike ‘real’ theatre you don’t have the excitement of sharing the same room with the actors but you do get to sit in a more comfortable seat – with some room to fidget – and you will get to see productions of a scale and ambition that local companies are unable to match.

If you’re one of those people who for one reason or another doesn’t go to theatre, you could do worse than trying Company, or one of the brilliant NTLive productions beamed in from the National Theatre on London’s South Bank. Unlike ‘real’ theatre you don’t have the excitement of sharing the same room with the actors but you do get to sit in a more comfortable seat – with some room to fidget – and you will get to see productions of a scale and ambition that local companies are unable to match.

There’s no New Zealand professional theatre company that would dream of mounting She Stoops to Conquer – Goldsmith’s 1773 satire on class, gender and age conflict – but you can trot along to your local cinema and see the wonderfully funny current production for approximately 1% of the cost of a return flight to London.

Coincidentally, David Cronenberg’s new film A Dangerous Method started life as a stage play. It was called The Talking Cure and has been adapted for the screen by its original writer, Christopher Hampton (Atonement). The play was, in turn, based on a book by John Kerr called A Most Dangerous Method which told the story of the relationship between Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen) and Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) and the birth of psychoanalysis at the beginning of the last century. This is potentially fascinating territory – particularly when you introduce Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley), a young woman who is initially treated by Jung for sexual neurosis and then becomes his colleague, his lover and finally his ex-lover.

Coincidentally, David Cronenberg’s new film A Dangerous Method started life as a stage play. It was called The Talking Cure and has been adapted for the screen by its original writer, Christopher Hampton (Atonement). The play was, in turn, based on a book by John Kerr called A Most Dangerous Method which told the story of the relationship between Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen) and Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) and the birth of psychoanalysis at the beginning of the last century. This is potentially fascinating territory – particularly when you introduce Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley), a young woman who is initially treated by Jung for sexual neurosis and then becomes his colleague, his lover and finally his ex-lover.

Unfortunately, potentially fascinating is where A Dangerous Method remains as the film itself never quite climbs off the page. Cronenberg’s common theme of body-horror – “the self-annihilating nature of the sexual act” as Freud puts it – is given a psychological twist so you can see why he was interested, but the closing title cards seem to imply that most of the drama happens to the characters after the film has finished.

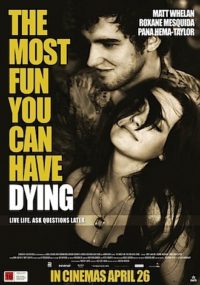

New Zealand director Kirstin Marcon’s debut film The Most Fun You Can Have Dying is visually assured but fails the plausibility test on almost every level – so much so that I’m inclined to think of it as the morphine-induced fantasy of a dying young man rather than try and take it at face value.

New Zealand director Kirstin Marcon’s debut film The Most Fun You Can Have Dying is visually assured but fails the plausibility test on almost every level – so much so that I’m inclined to think of it as the morphine-induced fantasy of a dying young man rather than try and take it at face value.

Matt Whelan (My Wedding and Other Secrets) plays Michael, from Hamilton, who is told that liver cancer means he has only a couple of months to live unless he can find $200,000 for a dangerous experimental treatment with only a 10% chance of sucess. His community raises him the money but – feeling manipulated and used – he takes the cash and heads to Europe for a wild last-chance OE.

The film feels disjointed – like there are pieces missing – and Michael’s selfishness and narcisissm would be pretty hard to watch for 90 minutes if it wasn’t for Whelan’s presence. He’s going places this one – our next Cliff Curtis, mark my words.

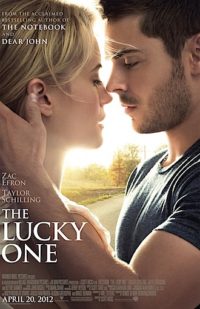

Finally, the truly ghastly The Lucky One which asks you to believe in Disney song and dance man Zac Efron as a traumatised Marine veteran of the Iraq War. Efron’s character Logan is a paragon of a man: an animal lover and humanitarian, war hero and philosopher, musician, engineer and handyman. The kind of man who would give the rest of us a bad name if he, you know, actually existed. His love interest, Taylor Schilling, does a lot of mouth-open acting and is shot – like everything else in the film – to look as pretty as possible regardless of the needs of story or character.

Finally, the truly ghastly The Lucky One which asks you to believe in Disney song and dance man Zac Efron as a traumatised Marine veteran of the Iraq War. Efron’s character Logan is a paragon of a man: an animal lover and humanitarian, war hero and philosopher, musician, engineer and handyman. The kind of man who would give the rest of us a bad name if he, you know, actually existed. His love interest, Taylor Schilling, does a lot of mouth-open acting and is shot – like everything else in the film – to look as pretty as possible regardless of the needs of story or character.

The Lucky One is some knucklehead’s idea of a dramatic situation – that knucklead being Nicholas “Dear John ” Sparks – but Sondheim’s Company has more drama, more character, more spirit, more life, in one lyric than you’ll find in this entire feature.

Printed in Wellington’s Capital Times on Wednesday 25 April, 2012.