Has any rock group inspired – and paid for – as much cinema as the Rolling Stones? From Jean-Luc Godard’s Sympathy for the Devil to Scorsese’s gilded concert footage for Shine a Light in 2009, the Stones have woven themselves into film history at the same time as they became rock legends. The Maysles Brothers’ Gimme Shelter is even in the Criterion Collection and footage from it informs a central chapter in Brett Morgen’s documentary (auto)biography of the band, Crossfire Hurricane.

Has any rock group inspired – and paid for – as much cinema as the Rolling Stones? From Jean-Luc Godard’s Sympathy for the Devil to Scorsese’s gilded concert footage for Shine a Light in 2009, the Stones have woven themselves into film history at the same time as they became rock legends. The Maysles Brothers’ Gimme Shelter is even in the Criterion Collection and footage from it informs a central chapter in Brett Morgen’s documentary (auto)biography of the band, Crossfire Hurricane.

As the 1969 Altamont free concert deteriorates into murderous anarchy, the still-living Stones provide their own 40-year-on perspective in croaky voiceover and it’s these audio-only reminiscences that provide the main novelty of a film that – at only two hours – struggles to contain the full majesty of “the greatest rock and roll band in the world”. There’s plenty of unseen (by me at any rate) new backstage and behind-the-scenes footage too, in an intricately edited portrait which is as honest as any band-authorised and Jagger-produced documentary is likely to be.

It’s easy to be tempted by the idea of the Sixties as an era of peace, love and harmony but the Stones story shows it to have been a vicious clash of generations where – under the shadow of the bomb – a nihilistic attachment to hedonistic good times is a totally understandable path for a sensitive young person to take. How Brian Jones became the band’s only permanent casualty is a medical mystery.

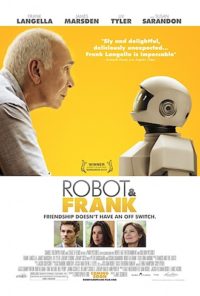

Rebellious ageing gets a different spin in Jake Schreier’s Robot & Frank, set in a near future where domestic robots can do more for us than just the dishes. Ageing former cat burglar Frank Langella, living a depressed retirement in upstate New York, is given a shiny white walking, talking appliance by his son (James Marsden). Resentful at first, his attitude changes when he discovers the machine (with the soothing voice of Peter Sarsgaard) has a talent for picking locks as well as no system-enforced legal boundaries. The subtext might land a little heavily in the final chapters (for some at least) but in general the film balances humour, satire and drama pretty well and Langella is just right.

Rebellious ageing gets a different spin in Jake Schreier’s Robot & Frank, set in a near future where domestic robots can do more for us than just the dishes. Ageing former cat burglar Frank Langella, living a depressed retirement in upstate New York, is given a shiny white walking, talking appliance by his son (James Marsden). Resentful at first, his attitude changes when he discovers the machine (with the soothing voice of Peter Sarsgaard) has a talent for picking locks as well as no system-enforced legal boundaries. The subtext might land a little heavily in the final chapters (for some at least) but in general the film balances humour, satire and drama pretty well and Langella is just right.

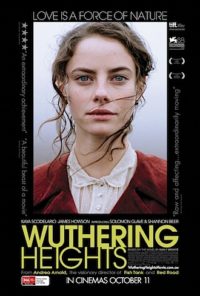

Andrea Arnold’s version of Wuthering Heights is much more challenging. Arnold is one of the great new voices in British cinema and Red Road and Fish Tank have shown her to be a kind of Ken Loach with added visual poetry. Wuthering Heights is a brave attempt to get under the skin of a well-known story and – even though I found it maddening at times – there are some wonderful moments.

Andrea Arnold’s version of Wuthering Heights is much more challenging. Arnold is one of the great new voices in British cinema and Red Road and Fish Tank have shown her to be a kind of Ken Loach with added visual poetry. Wuthering Heights is a brave attempt to get under the skin of a well-known story and – even though I found it maddening at times – there are some wonderful moments.

Arnold’s version of Heathcliff is a runaway slave, a stowaway child found on the streets of Liverpool and brought up in rural Yorkshire by the Earnshaws where he is brutalised by jealous oldest son Hindley and befriended by spirited daughter Cathy. Despite their relative poverty, his colour and his background mean that he will never be good enough to marry Cathy and his resentment grows into a tragic obsession. Dialogue isn’t really Arnold’s strong suit, so it’s good that there isn’t much apart from occasional clunky exposition. What Arnold does get – to a beautiful extent – is the Moors. Misty, rain-sodden, gorse-covered, moors – the interior made exterior.

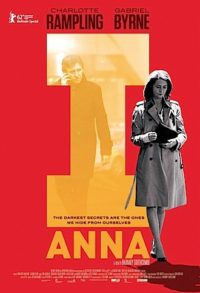

First-time feature director Barnaby Southcombe directs his mother, Charlotte Rampling, in the title role of I, Anna, a psychological thriller about a lonely woman embroiled in a murder mystery. Like Robot & Frank, the final twist lands with a thud rather than a splash but I, Anna also goes down a few blind alleys getting there. Gabriel Byrne is the insomniac cop who falls for the object of his investigation. There’s some interesting stuff going on here but the film itself screams for a bit of energy, to commit to it’s policier origins and let the subtext look after itself.

First-time feature director Barnaby Southcombe directs his mother, Charlotte Rampling, in the title role of I, Anna, a psychological thriller about a lonely woman embroiled in a murder mystery. Like Robot & Frank, the final twist lands with a thud rather than a splash but I, Anna also goes down a few blind alleys getting there. Gabriel Byrne is the insomniac cop who falls for the object of his investigation. There’s some interesting stuff going on here but the film itself screams for a bit of energy, to commit to it’s policier origins and let the subtext look after itself.

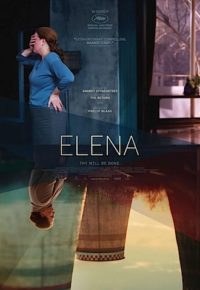

It has been sixteen months since I saw Elena at the 2011 International Film Festival so forgive me if this is a little vague on detail but I seem to recall that my considered reviewer’s opinion at the time was something like, “Blimey!”

It has been sixteen months since I saw Elena at the 2011 International Film Festival so forgive me if this is a little vague on detail but I seem to recall that my considered reviewer’s opinion at the time was something like, “Blimey!”

Elena (Nadezhda Markina) is married – for the second time – to a rich businessman with a heart condition. It seems like a fairly loveless arrangement in which she manages to divert a small amount of her husband’s wealth to her feckless son and grandchild. Her plans to buy the son out of his impending military service are threatened when her husband changes his will to include his own – previously estranged – daughter. What to do? The answer may surprise you but the cold-bloodedness of it will certainly affect you.

I found Elena to be stunningly amoral and the direction by genius Andrey Zvyagintsev (The Return, 2003) is chillingly antiseptic. It may have taken a year and a half to reach cinemas but it has been well worth the wait.

Printed in Wellington’s Capital Times on Wednesday 5 December, 2012.

Wuthering Heights is not a tale of true love yearning to break free from social convention, it’s a tale of passion unable to break into it. Heathcliff is not a dashing rebel, he’s a wild thing of a man, willing to sacrifice everything for schadenfreude. He’s the anti-Edward Cullen, if you must make the comparison, able to cave into lust but not any sexier for it. Wuthering Heights is the sort of romance we still need, just as much about the perils of emotional connections as it is about their catharsis. This is a movie that doesn’t end with a wedding. It ends the same kind of abject misery that most love stories do. It’s about your last break up, writ large over the swath of a lifetime, with all the seedy desires stymied and all the hurtful things you momentarily wished you had done fully enacted in all their horrible simplicity.