The first of the cars I got to test drive for FishHead magazine, the $170,000 BMW M3. It has been nearly four months since I posted something other than a…

Read More

In Gerard Johnstone’s tightly put together comedy-chiller Housebound, Morgana O’Reilly plays rebel-without-a-cause Kylie, forced by a judge to spend nine months of home detention with a mother she detests in…

Read More

As they say in the movies, "It's quiet... too quiet." Yeah, sorry about that but I've had a lot on recently. Here's the deal. In October last year (2013 if…

Read More

When we meet Texan man’s man Ron Woodroof (Matthew McConaughey) at the beginning of Dallas Buyers Club he is a mess – a shocking, disreputable, selfish combination of drunk, thief,…

Read More

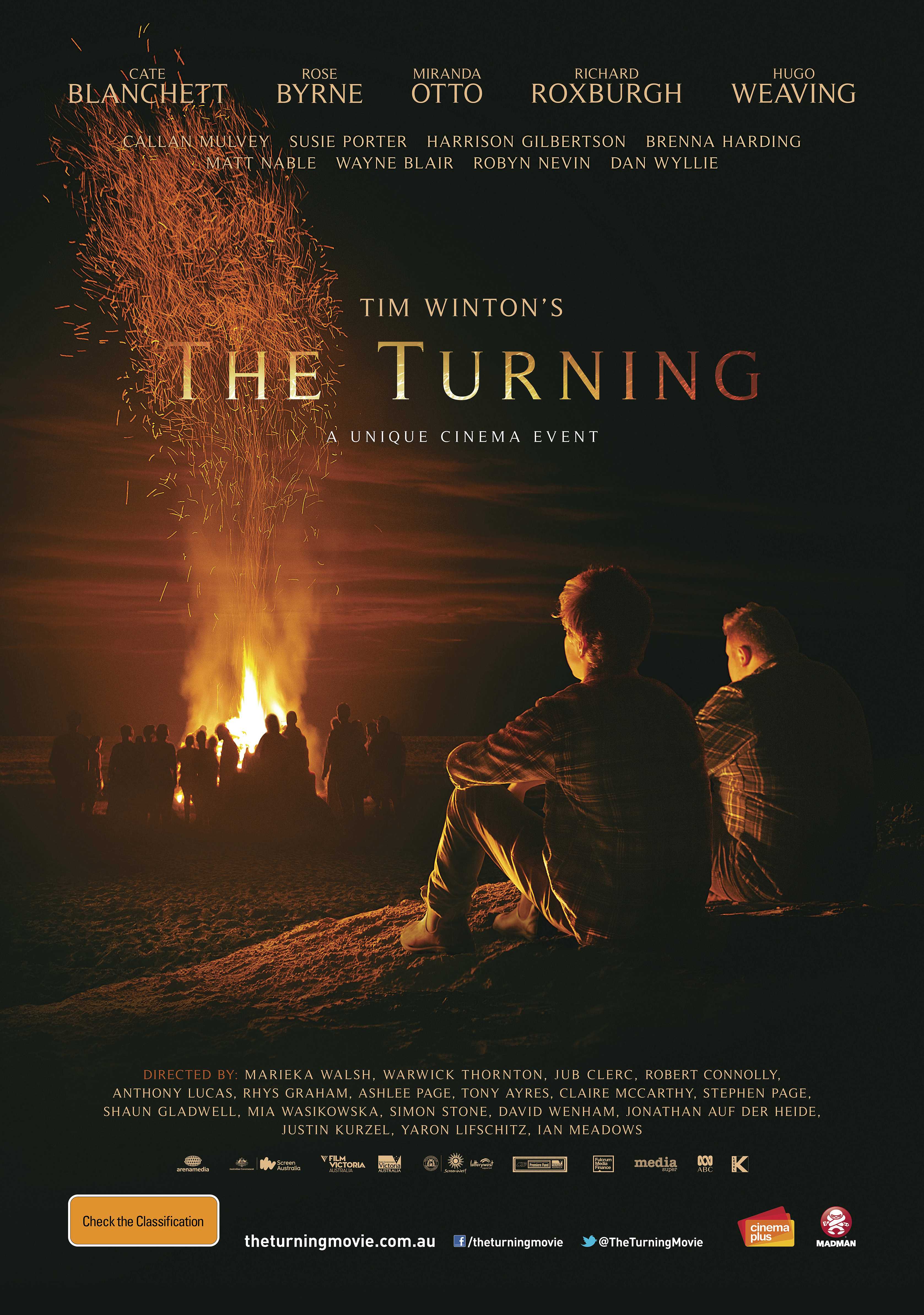

I went into The Turning in the dark and in some ways I wish I hadn’t and in others I’m glad I did. I’ll see if I can explain. The…

Read More

When did "late-period: Woody Allen start? Was it with Match Point (when he finally left New York for some new scenery)? Or should we consider these last ten, globe-trotting, years…

Read More