Of all directors currently working in the Hollywood mainstream Michael Mann is arguably the greatest stylist. No one at the multiplex has more control of the pure aesthetics of filmmaking, from colour balance and composition through editing and sound, Mann’s films (from Thief in 1981 to the misguided reworking of Miami Vice in 2006) have had a European visual sensibility while remaining heavily embedded in the seamy world of crime and punishment.

Of all directors currently working in the Hollywood mainstream Michael Mann is arguably the greatest stylist. No one at the multiplex has more control of the pure aesthetics of filmmaking, from colour balance and composition through editing and sound, Mann’s films (from Thief in 1981 to the misguided reworking of Miami Vice in 2006) have had a European visual sensibility while remaining heavily embedded in the seamy world of crime and punishment.

Now Mann has turned back the clock and made a period crime film, set during the last great depression. Based on the true story of the legendary bank robber John Dillinger, whose gang cut a swathe across the Midwest in 1933 and 1934, Mann’s Public Enemies is a stylish and superbly crafted tale of a doomed hero pursued by a dogged lawman. Dillinger is portrayed by Johnny Depp with his usual swagger and his nemesis is the now sadly ubiquitous Christian Bale.

Dillinger is a Robin Hood hero, a glamorous media star with matinée idol looks, sticking it to the “man”. The downtrodden masses, their own lives blighted by the hubris of high finance, don’t see much of a problem with bank robbery but, in the end, Dillinger’s downfall comes from a failure to adapt to changing times. As the crime syndicates get increasingly sophisticated, making their money from gambling and racketeering rather than robbery and kidnapping, they refuse to shelter Dillinger and his gang, fearful of the heat their presence brings.

And Heat is one of the reasons Public Enemies is less than the sum of its parts – the guts of this story was told by Mann in the 90s classic of the same name, the film that put Al Pacino and Robert De Niro on screen together for the first time (and which was itself a remake of another Mann film LA Takedown, made for TV in 1989). Not only is the arc of the story virtually identical, many of the set-pieces are the same (bank heists, shoot-outs) and he even repeats some of the same dialogue. Sadly, Mann may be a poet of the muzzle-flash and a supremely confident stylist but he doesn’t have much more to say than that the justice system is never as effective as the bullet of an honest man and I don’t know how interesting that is at the end of the day.

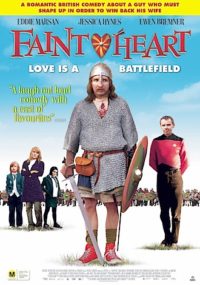

The great Eddie Marsan is the best and only reason to see Faintheart, a low budget British comedy about a medieval battle re-enactor and his stumbling attempts to live in the real world. You may not know Marsan’s name, but his face will be familiar to you from dozens of excellent supporting performances for directors like Mike Leigh, Alejandro González Iñárritu and even Michael Mann (in the aforementioned Miami Vice). Never less than totally committed, Marsan’s jowly countenance and soulful eyes gives all of his loser characters more depth than you find on the page which makes him perfect for this sort of thing. His wife has dumped him, his son is embarrassed by him and his best-friend (Trainspotting’s Ewan Bremner) is a clichéd Star Trek geek who works in a comic shop and still lives with his Mum.

The great Eddie Marsan is the best and only reason to see Faintheart, a low budget British comedy about a medieval battle re-enactor and his stumbling attempts to live in the real world. You may not know Marsan’s name, but his face will be familiar to you from dozens of excellent supporting performances for directors like Mike Leigh, Alejandro González Iñárritu and even Michael Mann (in the aforementioned Miami Vice). Never less than totally committed, Marsan’s jowly countenance and soulful eyes gives all of his loser characters more depth than you find on the page which makes him perfect for this sort of thing. His wife has dumped him, his son is embarrassed by him and his best-friend (Trainspotting’s Ewan Bremner) is a clichéd Star Trek geek who works in a comic shop and still lives with his Mum.

When the cocky PE teacher takes a shine to his Ex (Jessica Hynes from “Spaced”), Marsan’s Richard is forced to find the true strength of the Viking warrior in order to vanquish the usurper and reunite the family. All cobblers, of course, but sporadically entertaining.

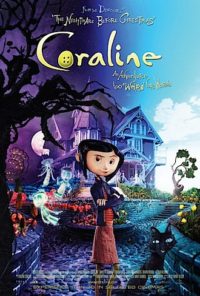

Regular readers will know that I have been a staunch cheerleader for 3D and digital screening technology, waiting impatiently for an artist with vision to use the format to create fresh and exciting works of art. Last year’s 3D re-mastering of Henry Selick’s The Nightmare Before Christmas gave us a hint of what he might be able to offer and he’s delivered in spades with Coraline, the first great 3D movie (or at least the first movie that is great because of the use of 3D).

Regular readers will know that I have been a staunch cheerleader for 3D and digital screening technology, waiting impatiently for an artist with vision to use the format to create fresh and exciting works of art. Last year’s 3D re-mastering of Henry Selick’s The Nightmare Before Christmas gave us a hint of what he might be able to offer and he’s delivered in spades with Coraline, the first great 3D movie (or at least the first movie that is great because of the use of 3D).

Selick’s traditional stop-motion techniques are used here, with digital fortification, to tell a spooky story about a young girl dragged away to a house in the country by self-obsessed parents. Left to her own devices she breaks through a sealed-off cupboard in her bedroom to find a parallel universe that is much more exciting and entertaining than her own. Almost too late she discovers that there are sacrifices that must be made if she is to remain. Coraline may be a bit too scary for the youngest, but otherwise is recommended as a tremendously imaginative piece of cinema magic.

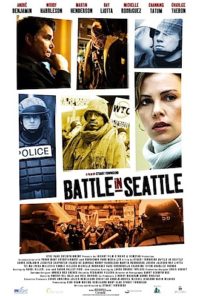

Best know to New Zealand audiences as the original Aragorn (replaced by Viggo after a week on Lord of the Rings) and to the rest of the world as Charlize Theron’s husband, Stuart Townsend proves himself a very able writer-director with Battle in Seattle, a ripped-from-the-headlines drama about the first great modern conflict between the forces of global capitalism and the treehuggers and peaceniks of the anti-everything movement at the 1999 World Trade Organisation meeting. Townsend skilfully recreates the mood of the time and, using fictionalised composite characters, manages to give some hints of the complexities surrounding the various issues which is no mean feat. Bonus points for running just under an hour a half too.

Best know to New Zealand audiences as the original Aragorn (replaced by Viggo after a week on Lord of the Rings) and to the rest of the world as Charlize Theron’s husband, Stuart Townsend proves himself a very able writer-director with Battle in Seattle, a ripped-from-the-headlines drama about the first great modern conflict between the forces of global capitalism and the treehuggers and peaceniks of the anti-everything movement at the 1999 World Trade Organisation meeting. Townsend skilfully recreates the mood of the time and, using fictionalised composite characters, manages to give some hints of the complexities surrounding the various issues which is no mean feat. Bonus points for running just under an hour a half too.

Printed in Wellington’s Capital Times on Wednesday 5 August, 2009.

Nature of conflict: Battle in Seattle is distributed in New Zealand by Arkles Entertainment who I do bits and pieces of work for every now and then.

Notes on screening conditions: Battle in Seattle was a screener DVD courtesy of Arkles; Public Enemies was screened at the Empire in Island Bay to the public on a Saturday night; Faintheart was a DVD played to the public in the Vogue Lounge of the Penthouse – very poor presentation, standard definition and you could even see the layer change half way through – and Coraline was screened at a special Sunday morning preview back in March courtesy of Readings management. Thanks to them for that.