When did “late-period: Woody Allen start? Was it with Match Point (when he finally left New York for some new scenery)? Or should we consider these last ten, globe-trotting, years as late‑r Woody? The last ten years have certainly been up and down in terms of quality. Scoop was all-but diabolical. Vicky Cristina Barcelona was robust and surprising. Midnight in Paris was genial but disposable (despite being a massive hit) and You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger was barely even a film.

Now, Blue Jasmine, in which Mr. Allen uses the notorious Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi crimes as inspiration for a story about the fraud’s victims as well as the collateral damage inflicted on a woman oblivious of her own complicity. As the eponymous Jasmine, Cate Blanchett plays the wife of Alec Baldwin’s shonky NY businessman, their relationship told in flashback while she tries to rebuild her life in her adopted half-sister’s (or something – the relationship seems unnecessarily complicated for something that has no material impact on the story) apartment in an unfashionable area of San Francisco.

Now, Blue Jasmine, in which Mr. Allen uses the notorious Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi crimes as inspiration for a story about the fraud’s victims as well as the collateral damage inflicted on a woman oblivious of her own complicity. As the eponymous Jasmine, Cate Blanchett plays the wife of Alec Baldwin’s shonky NY businessman, their relationship told in flashback while she tries to rebuild her life in her adopted half-sister’s (or something – the relationship seems unnecessarily complicated for something that has no material impact on the story) apartment in an unfashionable area of San Francisco.

There are some surprising pleasures to be had in the third attempted re-working of Vin Diesel’s Riddick franchise, mainly the choice to take it back to its gritty Pitch Black roots. Disposing of the overblown mythology of The Chronicles of Riddick (2004) in less than 90 seconds of awkward exposition featuring Karl Urban, we soon find ourselves back on a deserted desert planet in which Mr. Diesel’s wanted man proves himself to be Bear Grylls in space.

There are some surprising pleasures to be had in the third attempted re-working of Vin Diesel’s Riddick franchise, mainly the choice to take it back to its gritty Pitch Black roots. Disposing of the overblown mythology of The Chronicles of Riddick (2004) in less than 90 seconds of awkward exposition featuring Karl Urban, we soon find ourselves back on a deserted desert planet in which Mr. Diesel’s wanted man proves himself to be Bear Grylls in space.

A distress beacon only serves to bring two gangs of bounty hunters who then fight over who gets to take Riddick home while the approaching storm brings with it some ugly creatures who don’t much care whose side anyone is on. The other chief pleasure in the film is a performance by Australian (and former League star) Matt Nable who has a great face and an encouraging stillness.

As they used to say on television about kittens, “a child isn’t just for Christmas, a child is forever.” If only the utterly self-absorbed parents in What Maisie Knew had even seen that warning, let alone heeded it. Played with notable lack of personal ego, Julianne Moore and Steve Coogan are the battling parents of seven-year-old Maisie (Onata Aprile).

As they used to say on television about kittens, “a child isn’t just for Christmas, a child is forever.” If only the utterly self-absorbed parents in What Maisie Knew had even seen that warning, let alone heeded it. Played with notable lack of personal ego, Julianne Moore and Steve Coogan are the battling parents of seven-year-old Maisie (Onata Aprile).

She is a fading rock star and he is an international art dealer. Shown almost exclusively from little Maisie’s eye level, their bickering and biliousness can only end one way – the divorce court. Shuttled between Mum’s instant new bartender husband (Alexander Skarsgård) and Dad’s new wife, the former nanny played by Joanna Vanderham, Maisie’s natural robustness and good nature is severely put to the test and audiences with any kind of sensitivity will be on the edge of their seat as the parenting gets worse and worse.

I imagined What Maisie Knew as a kind of Before Midnight from the twin girls’ point of view. What happens to kids who grow up surrounded by meanness, aggression, verbal violence, selfishness with the occasional unexpected blurtings of love and affection in the form of spoilage. Adapted and updated brilliantly by Nancy Doyne and Carroll Cartwright from the novel by Henry James, this is a marvellous film that only occasionally tiptoes into melodrama but never loses sight of who the most important character is. You will care even if the parents don’t.

Probably already disappeared from local screens but worth keeping on your radar nevertheless, Romeo and Juliet: A Love Song is a rock opera version of the great tragedy, set in a Kiwi holiday park and directed with considerable music video panache by Tim van Dammen. If you appreciate Michael O’Neill and Peter Van Der Fluit’s songs as witty parodies of modern pop styles of the past 30 years you might get as much pleasure out of the film as I did. At least, I hope they were parodies.

Probably already disappeared from local screens but worth keeping on your radar nevertheless, Romeo and Juliet: A Love Song is a rock opera version of the great tragedy, set in a Kiwi holiday park and directed with considerable music video panache by Tim van Dammen. If you appreciate Michael O’Neill and Peter Van Der Fluit’s songs as witty parodies of modern pop styles of the past 30 years you might get as much pleasure out of the film as I did. At least, I hope they were parodies.

We have mentioned Jess Feast’s documentary Gardening With Soul on a couple of previous occasions in these pages so it will come as no surprise to find that I am offering a hearty, but belated, endorsement here now. A year in the life of witty, wise and wonderful Sister Loyola Galvin, the nun who runs the large garden for the Sisters of Compassion in Island Bay, this film makes a terrific companion piece to Christopher Pryor and Miriam Smith’s How Far Is Heaven which looked at another side of the sisters’ work last year.

Sister Loyola is a treasure and this is what local cinema can do so well – celebrating our heroes and our role models because if we don’t do it nobody from overseas is going to do it for us. A quiet triumph.

When I wrote my 2013 Film Festival Preview, Behind the Candelabra was not going to return to cinemas. Now it has, so I direct you to what I wrote back then which remains true today.

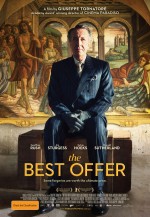

Giuseppe Tornatore once made Cinema Paradiso, a film beloved of cinephiles because it somehow transformed how we all feel about going to the movies into pictures. His high points since then have both been puzzles – in A Pure Formality (1994) Depardieu and Polanski spar during a mysterious police interrogation and, more recently, in The Unknown Woman a Ukrainian immigrant in Rome discovers the truth about her enigmatic past.

Giuseppe Tornatore once made Cinema Paradiso, a film beloved of cinephiles because it somehow transformed how we all feel about going to the movies into pictures. His high points since then have both been puzzles – in A Pure Formality (1994) Depardieu and Polanski spar during a mysterious police interrogation and, more recently, in The Unknown Woman a Ukrainian immigrant in Rome discovers the truth about her enigmatic past.

His latest, The Best Offer, is similarly constructed and characteristically classically photographed. Geoffrey Rush plays a kind of rock star auctioneer and art/antiquities expert drawn against his instincts into an intrigue featuring a villa full of old things and their owner, an agoraphobic author of romantic fiction. Rush has his own little psychological idiosyncrasies, though, but as he loosens up he fails to wonder whether he is letting his curiosity gets the better of him. Diverting and attractive but less than meets the eye.

[Portions of this review first appeared in Wellington’s FishHead magazine in September 2013.]